Women leaders weren't magically better at handling COVID

Bad arguments for good things are still bad arguments

This edition of Bracket is going out to 51 subscribers. Thank you for reading!

This article, like all Bracket goodness, is too big for email. Please click on the title above to open and read in your browser.

On the 21st of March 2020, New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern made an address to the nation1. “Over the past few weeks, the world has changed. And it has changed very quickly.”, she said. “[…] we are experiencing an unprecedented event – a global pandemic - that in New Zealand, we have moved to fight by going hard, and going early. […] today I am going to set out for you as clearly as possible what you can expect as we continue to fight the virus together.”

Her address set New Zealand at level two in a four-level alert system for COVID response. Four days later, she announced they were at level four2. New Zealand was in lockdown. It was probably the earliest high-profile success of the pandemic. “Her leadership style is one of empathy in a crisis that tempts people to fend for themselves.”, one early profile read3. “Her messages are clear, consistent, and somehow simultaneously sobering and soothing. And her approach isn’t just resonating with her people on an emotional level. It is also working remarkably well.”

These high-profile stories quickly formed a pattern: that countries led by female leaders did better at containing the pandemic than male-led countries. This even got academic attention. A preprint was published by UK researchers Garikipati and Kambhampati, in June 20204, later published as a paper5, which said their findings showed “that COVID-outcomes are systematically and significantly better in countries led by women”. Another paper was published in June by University of Michigan researchers6, which concluded that female leaders had an edge over their male counterparts, though this was not a statistically significant result.

It was also quickly a part of the mainstream media discourse: it was written about by literally every mainstream news publication you can name. The headlines read like a randomly selected Twitter feed. “What the pandemic reveals about the male ego”, one said. “Women are better leaders”, CNN declared. “The pandemic proves it”. “The COVID crisis shows why we need more female leadership”, argued Fortune, discussing Garikipati and Kambhampati’s research7.

Why might this be? “women tend to adopt a more transformational leadership style”, CNN wrote, “which includes demonstrating compassion, care, concern, respect and equality. In contrast, men have a more transactional approach, which includes a more task-focused, achievement-oriented and directive style of management.”

“Women are more likely to develop flatter, more democratic management structures, and prioritize ‘clear and decisive communications’ and personal relationships.” according to Fortune. “These factors make teams and nations alike more agile by inviting diverse input, allowing for faster and locally informed decision-making, and enhancing accountability.”

There’s one problem with all of this: it’s bullshit. The correlation - to the extent it existed - was spurious. This has been studied by different researchers since, and on the whole there doesn’t seem to be a global difference due to the gender of leader, unless you select really specific countries and squint really hard. The coverage was mostly gender-essentialist garbage. At the very least, none of this research merits anywhere near the certainty that was displayed.

Garikipati and Kambhampati wrote a column for CEPR in June 2020 based on their research. It was titled “Women leaders are better at fighting the pandemic”.

Think about what the issues with a potential analysis of this question would be. Different standards of data quality and transparency would be a problem, and this was obvious right from the start of the pandemic8. Another would be the relative lack of female leaders: by my count off Wikipedia9, 22 women served as national leaders in March 2020, and 13 of them were actually in an Executive role. (This is an important distinction missed by a lot of coverage). In either case, the UN currently recognises 193 countries (excluding Taiwan, whose female president was another of the early high-profile success stories). This is too few. The next problem would be changes in leadership: as outlined in detail here, lots of countries changed leaders in the middle of pandemic. Belgium replaced Sophie Wilmes with Alexander De Croo on 1st October 202010, switching columns. Lithuania replaced Saulius Skvernelis with Ingrida Šimonytė in December11. Estonia replaced Jüri Ratas with Kaja Kallas in January, with seemingly no concern for our analysis. Some of these countries had different COVID outcomes before and after. Which column should they count in?

If one of our groups has 13 countries, these seemingly small, random changes start making really big differences. And then there are the not-so-obvious problems: testing for a lot of variables on one dataset can be like fishing with a trawler instead of a rod, where you dredge up everything that moves and throw away what you don’t like.

Every analysis on this topic, whether they talked about it or not, had to grapple with these problems, obvious to even the non-academic. Chang (2022) and Hendrix (2021) both conclude female-led countries did better, but their articles both have particular issues of selection bias, as outlined in detail here.12 Chang and colleagues are not transparent about country choice, and they’re analysing 21 factors for 99 countries, with higher risk for finding spurious correlations. Hendrix classifies countries as female-led even in cases where they had largely ceremonial posts, or were replaced by a man halfway through, in a sample of eight female countries and twenty total.

Aldrich and Lotito13 found no significant difference between female-led and male-led countries in instituting stay-at home orders, or information campaigns. Mette Harder and Christoffer Harder14 found that female leaders didn’t introduce faster or more extensive shutdowns, unless you narrowed it down to OECD countries. Bauer and colleagues15 found from a survey that people weren’t more or less likely to comply with orders based on the leader’s gender. Bishu and colleagues16 conducted a survey in eight US states, and found that the governor’s gender had no effect on people’s protective actions (they did find something interesting but tangential: that female conservative leaders were perceived as being more competent).

Coscieme and colleagues17 found that countries with female leaders had better COVID outcomes than male-led countries, but they found this in their subset of 35 high-income democracies (some of their criteria could lead to bias, like excluding Thailand and Sri Lanka for not having a peak in deaths in their time period). They concluded this was for two reasons: because of specific policies undertaken by those politicians, and because being female-led was often a marker of more equal societies.

Windsor and colleagues18 found female-led countries had slightly better COVID death rates, though this was not statistically significant. But they didn't think this was due to some inherent trait of female leadership. "Women who lead these countries are able to successfully manage crises like the pandemic”, they wrote, “not because they are women but because they are leading countries more likely to elect women to the highest executive office in the first place, and because those countries have policy landscapes and priorities that pre-dispose them to manage risk better." Maity and Barlaskar analysed responses by Indian states, but given that only West Bengal had a chief minister, they used female representation in state legislatures, an interesting proxy for female participation in politics and social attitudes. With this proxy, they found states with higher female representation were more "efficient" in dealing with the pandemic.

Jennifer Piscopo19 argued that this correlation was spurious. "[...] many women-led countries score high on state capacity", she argued, "[and] high-capacity states have low coronavirus mortality regardless of whether they are led by women or by men." Abras and colleagues found a significant negative correlation with female heads of state. But they also found that “there is no evidence that countries led by women responded faster than countries led by men in implementing social distancing measures to “flatten” the infection curve, [and] countries led by women have a higher rate of universal healthcare coverage than countries led by men; if the countries led by men had comparable levels of investment in a widely available healthcare system, their outcomes from fighting the pandemic would be similar.”

Think about the success stories widely discussed in the media. All of them are high-income democracies in the global North. Iceland, New Zealand, and Taiwan are islands, easier to lock down. Norway, Finland, and Denmark are rich, homogeneous, low-population, high-social-trust Nordic countries. Germany is a developed Western country with high state capacity that you would expect to do well with any sudden crisis. Is the gender of the one person at the top the crucial factor here? Hell, as Hilda Bastian points out, had the pandemic hit a couple of years earlier than it did, Denmark and Finland would’ve also been male-led instead of female-led. Would their pandemic numbers have been hugely different?

When a group contains less than twenty countries, small differences start to matter a lot. We can perhaps look at how. Garikipati and Kambhampati’s paper relies on analysis of publicly available data that we can try to replicate.

In this section, I analyse some data to see how much the insights from this paper are generalisable. It can be skipped if that’s not your thing - skip over to the next marker in that case. I assume you have some understanding of means and standard deviations.

The authors rely on COVID data from Worldometer upto 19th May 2020. With the advantage of retrospect, I think Our World in Data is a better source, with a retrospective dataset by date. Data for GDPs, population, population over 65, etc is sourced from the World Bank dataset, same as the study. All the data and code used for this is on my GitHub here. Please let me know if I’ve made any errors.

The authors consider a list of 191 countries and 19 female-led countries where they argue the female leaders held an executive post. But when the pandemic hit, Wikipedia lists 22 female world leaders, and 13 of them were listed as executives. The six other countries that are considered female-led in this study aren’t listed. In a study that is this dependent on specific countries, this is a really important thing to be transparent about! For now, let’s run with the list of 13, and the overall list of 22.

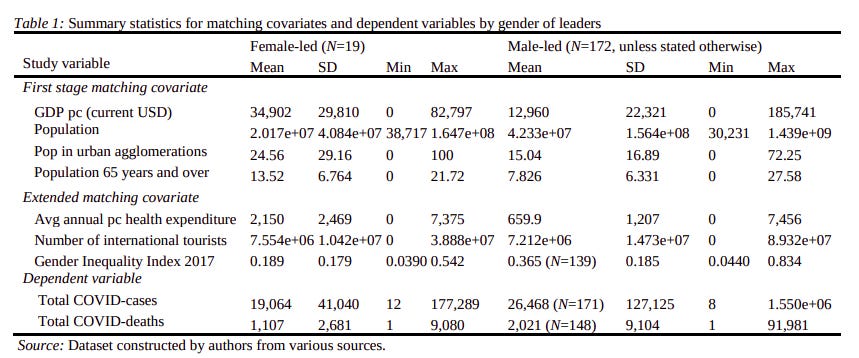

The first thing the authors present is a table of summary statistics, followed by a summary of the regression coefficients.

“Although these are raw statistics and not useful to draw inferences”, they argue, “it is clear that female-led countries have fared better in terms of absolute number of COVID-cases and deaths, with male-led countries having nearly double the number of deaths as female-led ones”.

Yes, the mean numbers of cases and deaths are different across male-led and female-led countries. But for female-led countries, the standard deviations are more than double the mean, indicating that the data is very dispersed and the mean isn’t a great single-point summary. For male-led countries, the standard deviations are four and five times the mean. At the very least, you should be asking other questions here.

And then the other variables in their table: female-led countries spend about thrice as much per capita on healthcare. They have thrice the GDP per capita. Population is the most significant predictor in the regression, because the outcome considered is total cases and not cases per capita.

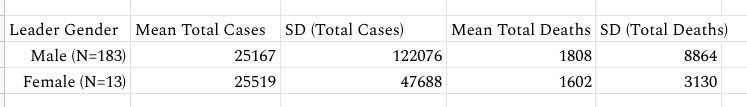

If you narrow this down to 13 countries where women were executive leaders, a large part of even this gap disappears, and the standard deviations are still embarrassingly large.

Here’s something funnier. If you include per capita cases and per capita deaths - a better measure when comparing countries - by numeric coincidence and poetic justice, this gap flips.

“[…] it is clear that female-led countries have fared better”? Are you kidding me?

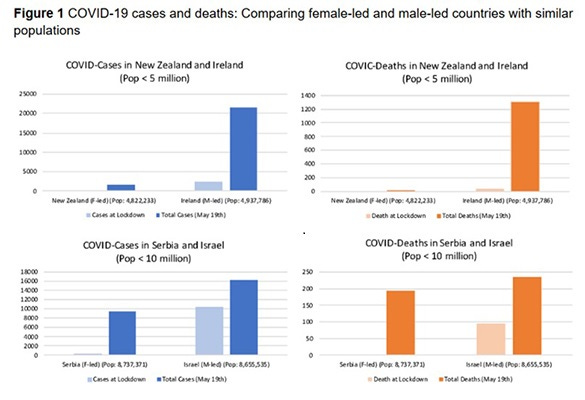

To get around the problem of small sample size, the authors then compare the female-led countries one by one to the country they assign as its nearest neighbour, in terms of four parameters: – GDP per capita, Population, urban population, and Population over 65. Now, every country faced unique dynamics at the start of the pandemic: island countries are generally easier to lock down than countries with porous land borders. That makes this risky business: whether you match New Zealand with Ireland or Macao could end up making a pretty large difference, especially with few countries to compare.

And that is what happens. The actual list of countries that were matched with each other is not included in the paper (another thing that’s really important to be transparent about!), but the authors included this chart in the press release accompanying the preprint:

Serbia and Israel were presumably mapped to each other in the study. Perhaps due to choosing 13 countries instead of 19, my nearest neighbour for Serbia is Lebanon, a country that is similar on the four metrics. And Lebanon’s cases and deaths are a lot fewer than Serbia’s at the time of measurement.

Here’s the table included in the paper comparing the countries to their nearest neighbours: (I’m really not certain about the methodology here, because it’s not provided in any detail in the paper itself or linked anywhere. I assume the authors are doing a t-test on the sample to check if the mean difference between nearest neighbours is less than 0).

Maybe as a result of the slightly different countries: this difference is a lot smaller in my dataset, and the significance disappears. Here’s a summary of my results:

It suddenly starts looking like the use of total cases and deaths as a metric and the choice of the 19 countries was driving a lot of the gap, doesn’t it? Doesn’t that just make you want to know, deep in your bones, the six additional countries?

The point of this is not to shit on particular researchers personally, though I believe this was an egregious example. It’s not to use hindsight to claim to know the answers, either (this is not an episode of The Newsroom). It is to point out that this is a quirk of the way this study is structured. The gap it shows only exists at a specific point in time, for a specific group, and disappears when you broaden the frame a little bit or get stricter with the definition of what a female leader is - all the hallmarks of a spurious correlation. And it is to plead that researchers stop overstating what their own numbers say for a soundbite.

The language of science can be inaccessible and sometimes really confusing, and it’s also often full of doubt. This can work against communicating the results of a scientific study (ask climate change researchers). But it is that way for a reason: uncertainty is inherent to the endeavour. In an assignment for a statistics course, my professor emphasised the need to elaborate how much you don’t know as much as what you know from the data available (“The goal is the best analysis that you can manage with the tools and data available to you, but you must therefore be honest and transparent when discussing the flaws of that analysis”). Why do actual researchers feel okay not doing the same thing? And where is the ability of the media to actually judge, understand, clarify in any capacity what they are reporting on? What if I keep talking rhetorical questions till you just can’t take it anymore?

In May 2021, about a year after this paper came out, two researchers at the LSE wrote an article called “It's a distraction to focus on the success of individual women leaders during Covid”20. I would paste it here word-for-word if I could. "...women’s representation”, they wrote, “is a symptom of a particular society that responds well in crisis likely owing to governance structures and social contract, just as women’s lack of representation is a symptom of the distance and inequality between governing structures and the people they are intended to serve. Women’s participation in politics is influenced by broader participation in the labour market, increased development, a post-industrial society and a developed welfare state. Analyses of individual women leaders should therefore be considered against the backdrop of broader equality in the social contract.”

When the pandemic hit, only 22 heads of state - executive or otherwise - were women. That’s about a tenth of all the world’s countries. Whatever you believe about whether women are naturally gifted to lead during pandemics, that is absurdly low for half of the world’s population. (For Indians, here’s the baseline: 14% and 11% of the legislators in India’s two houses of parliament are women.)

We need more women in government, because a government that represents all the diverse viewpoints and issues faced by the population is a good thing. We should work towards a society where men and women have equal opportunity to get into public office (or to do anything they want), where prejudices and sexism don’t limit what society lets you do based on your gender.

But these simplistic narratives about “5 girlboss leaders who #slayed the pandemic” help absolutely no one.

They’re bad because they’re based on a west-centric, laughably shallow understanding of the world. The interesting story here is that the gender of the leader is the tip of the iceberg. Countries that elect female leaders, or more importantly, countries where women are free to participate in their own government and their own economy - are often more capable states. It’s not some ‘women are from Venus’ type bullshit.

They’re bad because they often perpetuate really shitty narratives about men and women - that women are nurturing caregivers, and men are stoic, aggressive blocks of toxic masculinity. People - men and women - have been fighting these narratives for decades. For a reason. Using spurious correlations and shitty narratives in a good cause doesn’t make them okay; it hurts the cause.

They’re bad because they’re a case study of our superficial media ecosystem - a study came out, in this case a couple months into the pandemic, and a bunch of people wrote takes about it. Without actually being able to situate it with any kind of context, without being able to examine what they’re reading or clarify what they’re reporting on, even as “science” journalists. A larger discussion did take place, but it was largely academic, and went largely unnoticed. Because people were done writing takes about it, and they had moved on to the next Harry and Meghan adventure. As had the audience - us.

They’re bad because they raise the stakes for what women leaders are supposed to do. The leader of Belgium for the first six months of the pandemic - when they had the world’s highest death rate among countries with at least one lakh people - was Sophie Wilmes, who was replaced by a man in November 2020. If we should elect more women because New Zealand had great COVID numbers under Jacinda Ardern, does that mean we should boot women out of office and elect more men because Belgium had bad COVID numbers under Sophie Wilmes?

Which brings me to probably the weirdest thing I will say here: Allow female leaders to be bad at things, without it reflecting on their gender as a whole. Women can make bad decisions and mishandle situations (oh hi, Liz Truss!). Because they’re humans, and humans make bad decisions and mishandle situations sometimes. That is what this shitty argument does: it sets up ordinary women in leadership positions for failure, by judging their performance on a spurious correlation that can turn on a dime. When we place female leaders on a pedestal, we make the step harder for ordinary women.

Better representation of our society in our ruling classes is a good thing, because equality and justice and fairness are worthy values we should work towards. And that is enough.

Bad arguments are still bad arguments. Bad studies are still bad studies. Even when they support things you and I support.

https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2020/04/jacinda-ardern-new-zealand-leadership-coronavirus/610237/

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3617953

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13545701.2021.1874614

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.06.20124487v2.full

https://fortune.com/2021/03/17/covid-female-women-leadership-jacinda-ardern/

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/02/us/politics/cia-coronavirus-china.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_elected_and_appointed_female_heads_of_state_and_government

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_prime_ministers_of_Belgium

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prime_Minister_of_Lithuania

https://absolutelymaybe.plos.org/2022/06/28/women-versus-men-leaders-in-the-pandemic-an-update-and-dig-into-the-latest-data/

If there’s one thing you really want to read as a recap of this whole thing from a much more authoritative source, read this. I’ve relied heavily on Dr. Bastian’s work here, and she has been talking about this since 2020.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-gender/article/pandemic-performance-women-leaders-in-the-covid19-crisis/579B3EA9BE0CD8215EE2E74257252FED

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3679608

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-gender/article/women-leaders-and-policy-compliance-during-a-public-health-crisis/F0C1DD547BF83FF6C729B17AFC127C1A

https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/does-the-public-ignore-female-governors-on-the-covid-19-pandemic

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.13.20152397v2.full

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0244531

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-gender/article/women-leaders-and-pandemic-performance-a-spurious-correlation/69FA5BD035CEE66F0FFFC61DF037DD0E

https://www.kcl.ac.uk/news/individual-women-leaders-covid

![[bracket]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!YRIN!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7982c3aa-3a4d-41d9-8681-2abd1ecd6d6c_529x529.png)

![[bracket]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!YRIN!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7982c3aa-3a4d-41d9-8681-2abd1ecd6d6c_529x529.png)